The Home Monthly

From The Home Monthly, VI (September 1896): 9-11.

The Count of Crow's Nest.

ILLUSTRATIONS BY FLORENCE PEARL ENGLAND.CROW'S NEST was an over-crowded boarding house on West Side, over-crowded because there one could obtain shelter and sustenance of a respectable nature cheaper than anywhere else in ante-Columbian Chicago. Of course the real name of the place was not Crow's Nest; it had, indeed, a very euphuistic name; but a boarder once called it Crow's Nest, and the rest felt the fitness of the title, so after that the name clung to it. The cost of existing had been reduced to its minimum there, and it was for that reason that Harold Buchanan found the Count de Koch among the guests of the house. Buchanan himself was there from the same cause, a cause responsible for most of the disagreeable things in this world. For Buchanan was just out of college, an honor man of whom great things were expected, and was waiting about Chicago to find a drive wheel to which to apply his undisputed genius. He found this waiting to see what one is good for one of the most trying tasks allotted to the sons of men. He hung about studios, publishing houses and concert halls hunting a medium, an opportunity. He knew that he was gifted in more ways than one, but he knew equally well that he was painfully immature, and that between him and success of any kind lay an indefinable, intangible something which only time could dispose of. Once it had been a question of which of several professions he should concentrate his energies upon; now the problem was to find any one in which he could gain the slightest foothold. When he had begun his search it was a quest of the marvelous, of the pot of fairy gold at the rainbow's end; but now it was a quest for gold of another sort, just the ordinary prosaic gold of the work-a-day world that will buy a man his dinner and a coat to his back.

In the meantime, among the tragic disillusionments of his first hazard of fortune, Buchanan had to live, and this he did at Crow's Nest because existence was much simplified there, almost reduced to first principles, and one could dine in a sack coat and still hold up his head with assurance among his fellow men. So there he had his study, where he began pictures and tragedies that were never completed, and wrote comic operas that were never produced, and hated humanity as only a nervous sensitive man in a crowded boarding house can hate it. The rooms above his were occupied by a prima donna who practised incessantly, a thin, pale, unhappy-looking woman with dark rings under her eyes, whose strength and salary were spent in endeavoring to force her voice up to a note which forever eluded her. On his left lived a discontented man, bearded like a lion, who had intended to be a novelist and had ended by becoming a very ordinary reviewer, putting the reproach of his failure entirely upon a dull and unappreciative public.

The occupants of the house were mostly people of this sort, who had come short of their own expectations and thought that the world had treated them badly and that the time was out of joint. The atmosphere of failure and that peculiar rancor which it begets seemed to have settled down over the place. It seemed to have entered into the very walls; it was in the close reception room with its gloomy hangings, clammy wall paper, hard sofas and bad pictures. It was in the old grand piano, with the worn yellow keys that clicked like castanets as they gave out their wavering, tinny treble notes in an ineffectual staccato. It was in the long, dark dining room, where the gas was burning all day, in the reluctant chairs that were always dismembering themselves under one, in the inevitable wan chromo of the sad-eyed Cenci who is daily martyred anew at the bands of relentless copyists, in the very clock above the sideboard whose despairing, hopeless hands never reached the hour at the proper time, and which always struck plaintively, long after all the other clocks were through.

The prima donna sneered at the chilly style of the great Australian soprano who was singing for a thousand dollars a night down at the Auditorium, the reviewer declared that literature had stopped with Thackeray, the art student railed day and night against all pictures but his own.

Buchanan sometimes wondered if this were a dark prophecy of his own future. Perhaps he, too, would some day be old and poor and disappointed, would have touched that wall which marks the limitations of men's lives, and would hate the name of a successful man as the dwarfs of the underworld hated the giants in the golden groves of Asgard. He felt it would be better to contrive to get capsized in the lake some night. Could there be any greater degradation than to learn to hate an art and its exponents merely because one had failed in it himself? He fervently hoped that some happy accident would carry him off before he reached that stage.

Day after day he sat down in that dining room that was so conducive to pessimistic reflection, with the same distasteful people: The blonde stenographer who giggled so that she often had to leave the table, the cadaverous art student who talked of originating a new school of landscape painting, and who meantime taught clay modeling in a design school to defray his modest expenses at the Nest, the reviewer, the prima donna, the languid old widow who wore lilacs in her false front and coquetted with the fat man with the ear trumpet. She had, in days gone by, made coy overtures to Buchanan and the surly reviewer, but as they were more than unresponsive and would have none of her, she now devoted herself exclusively to the deaf man, though undoubtedly ear trumpets are an impediment to coquetry. But as the deaf man could not hear her at all, he stood it very well. He might also be short sighted, Buchanan reflected.

In all that vista of faces, there were some twenty in all, there was but one which

was

not unpleasant; that of the courtly old gentleman who ate alone at a small table at

the

end of the dining room.

"A GENTLEMAN AMONG CANAILLE."

He was only there at dinner, his breakfast and luncheon were

always sent to his room. He had no acquaintances in the house and spoke to no one,

yet

every one knew that he was Paul, Count de Koch, and during breakfast and luncheon

hours he

and his possible history had furnished the pièce

de résistance of conversation

for some months. In that absorbing theme even the decadence of French art and English

letters and the execution of the Australian soprano were forgotten. The stenographer

called attention to the fact that his coat was of a prehistoric cut, though she

acknowledged its fit was above criticism. The widow had learned from the landlady

that he

shaved himself and blacked his own boots. She was certain he had been a desperately

wicked

man and lost all his money at Monte Carlo, for unless Counts were very reprehensible

indeed they were always rich. This scrutinizing gossip about a courteous and defenseless

old gentleman was the most harrassing of all Buchanan's table

trials, and it savored altogether too much of the treatment of Père Goriot in Madame

Vanquar's "Pension Bourgeoise."

"A GENTLEMAN AMONG CANAILLE."

He was only there at dinner, his breakfast and luncheon were

always sent to his room. He had no acquaintances in the house and spoke to no one,

yet

every one knew that he was Paul, Count de Koch, and during breakfast and luncheon

hours he

and his possible history had furnished the pièce

de résistance of conversation

for some months. In that absorbing theme even the decadence of French art and English

letters and the execution of the Australian soprano were forgotten. The stenographer

called attention to the fact that his coat was of a prehistoric cut, though she

acknowledged its fit was above criticism. The widow had learned from the landlady

that he

shaved himself and blacked his own boots. She was certain he had been a desperately

wicked

man and lost all his money at Monte Carlo, for unless Counts were very reprehensible

indeed they were always rich. This scrutinizing gossip about a courteous and defenseless

old gentleman was the most harrassing of all Buchanan's table

trials, and it savored altogether too much of the treatment of Père Goriot in Madame

Vanquar's "Pension Bourgeoise."

He was always glad at dinner when the Count's presence put a stop at least to audible queries, and his calm patrician face again made its strange contrast with the sordid unhappy ones about him. His clear gray eyes, his slight erect figure, and white, tapering hands seemed quite as anomalous there as his name. That gentlemanly figure made life at Crow's Nest possible to Buchanan; it was like seeing a Vandyke portrait in the gallery of daubs. The Count's whole conduct, like his person, was simple, dignified and artistic. It was a cause for much indignation among the boarders, particularly so in the case of the widow and prima donna, that he met no one. Yet his manner was never one of superiority, simply of amiable and dignified reserve. He might at all times have stood the scrutiny of a court drawing room, yet he was perfectly unostentatious and unconscious. There was something regal about his gestures. When he held back the swinging door for the hurried maid with her groaning tray of dishes, you half expected to see the Empress Eugenie and her train sweep through, or gay old Ludwig with his padded calves and painted cheeks and enormous wig, his troup of poets and dancers behind him. He drank his pale California claret as if it were Madeira of one of those priceless vintages of the last century.

In his college days Buchanan had been a good deal among well-bred people, but he had never seen any one so quietly and faultlessly correct. Sometimes he met him walking by the Lake Shore, and he thought he would have noticed his carriage and walk among a thousand. In watching him that phrase of Lang's, "A gentleman among canaille," constantly occurred to him.

One of the saddest defects of that ponderous machinery which we call society is the impenetrable wall which is built up between personalities; one of the saddest of our finite weaknesses is our incapacity to recognize and know and claim the people who are made for us. Every day we pass men who want us and whom we bitterly need, unknowing, unthinking, as friends pass each other at a masked ball: pursuing the tinkle of the harlequin's bells, not knowing that under the friar's hood is the camarâdéie they seek. Following persistently the fluttering hem of the priestly gown, never dreaming that the heart of gold is under the spangled corsage of Folly there, sitting tired out on the stairway. It seems as if there ought to be a floor manager to arrange these things for us. However, given a close proximity and continue it long enough, and the right people will find each other out as certainly as the satellites know their proper suns. It was impossible that, in such a place as Crow's Nest, Buchanan's relations to the Count should continue the same as those of the other boarders. It was impossible that the Count should not notice that one respectful glance that was neither curious nor vulgar, only frankly interested and appreciative.

One evening as Buchanan sat in the reception room reading a volume of Gautier's romances while waiting for the dinner that was always late, he glanced up and detected the Count looking over his shoulder.

"I must ask your pardon for my seeming discourtesy, but one so seldom sees those delightful romances read in this country, that for the moment I quite forgot myself. And as I caught the title 'La Morte Amoureuse,' an old favorite of mine, I could scarcely refrain from glancing a second time."

Buchanan decided that since chance had thrown this opportunity in his way, he had a right to make the most of it. He closed the book and turned, smiling.

"I am only too glad to meet some one who is familiar with it. I have met the idea before, it has been imitated in English, I think."

"Ah, yes, doubtless. Many of those things have been imitated in English, but—"

He shrugged his shoulders expressively. "Yes, I understand your hiatus. These things are quite impossible in English, especially the one we are speaking of. Some way we haven't the feeling for absolute and specific beauty of diction. We have no sense for the aroma of words as they have. We are never content with the effect of material beauty alone, we are always looking for something else. Of course we lose by it, it is like always thinking about one's dinner when one is invited out."

The Count nodded. "Yes, you look for the definite, whereas the domain of pure art is always the indefinite. You want the fact under the illusion, whereas the illusion is in itself the most wonderful of facts. It is a mistake not to be content with perfection and not find its sermon sufficient. As opposed to chaos, harmony was the original good, the first created virtue. And of course a great production of art must be the perfection of harmony. Even in the grotesque the harmony of the whole must be there. To be impervious to this indicates a certain bluntness toward the finer spiritual laws."

"And yet," said Buchanan, "we have been accustomed to look at all this as quite the opposite of spiritual. Our standpoint is certainly rather inconsistent, but I believe it is honest enough."

The Count smiled. "Certainly. It is a question of whether you want your sermon in a flower or in a Greek word, in poetry or in prose, whether you want the formula of goodness or goodness itself. So many of your authors write formulae. There was, however, one of your littérateurs who knew the distinction, even if he was something of a charlatan in using it. Poe surpassed even Gautier in using some effects of that character," pointing to the book in Buchanan's hand. "Perhaps under happier circumstances he might have done so in all. You had there a true stylist, who knew the value of an effect; a master of single and graceful conceptions, who was content to leave them as such, unexplained and without apology."

"Perhaps that is the reason we say he was crazy," said Buchanan, sadly.

"Perhaps," said the Count as he lighted his cigar. "I hope to have the pleasure of discussing this again with you. You have read 'Fortunio?' No? When you have read 'Fortunio' I will wish to see you." He smiled and went out for his wintery walk on the Lake Shore.

After that Buchanan met the Count frequently, in the hallway, on the veranda, on his

walks. They always had some conversation during these encounters, but their remarks

were

generally of a very casual nature. Buchanan felt some hesitancy about pushing the

acquaintance lest he should exhaust it too soon. His tendency had always lain

"A TALL BLONDE WOMAN, DRESSED IN A TIGHT-FITTING TAILOR-MADE GOWN, WITH A PAIR OF

LONG LAVENDAR GLOVES LYING JAUNTILY OVER HER SHOULDER, ENTERED AND BOWED GRACIOUSLY

TO THE COUNT."

that way. In

his intemperate youth he had plunged hot-headed and rapacious into friendship after

friendship, giving more than any one cared to receive and exacting more than any one

had

leisure to give, only to reach that almost inevitable point where, independent of

any

volition of his own, the impetus slackened and stopped, the wells of sweet water were

dry

and the cisterns were broken. These promising oases that flourish among monotonous

humanity dry up so quickly, most of them. They are verdant to us but a night. There

are so

few minds that are fitted to race side by side, to wrestle and rejoice together, even

unto

the paean. And after all that is the base of affinities, that mental brotherhood.

The

glamour of every other passion and enthusiasm fades like the brilliance of an afterglow,

leaving shadow and chill and a nameless ennui.

"A TALL BLONDE WOMAN, DRESSED IN A TIGHT-FITTING TAILOR-MADE GOWN, WITH A PAIR OF

LONG LAVENDAR GLOVES LYING JAUNTILY OVER HER SHOULDER, ENTERED AND BOWED GRACIOUSLY

TO THE COUNT."

that way. In

his intemperate youth he had plunged hot-headed and rapacious into friendship after

friendship, giving more than any one cared to receive and exacting more than any one

had

leisure to give, only to reach that almost inevitable point where, independent of

any

volition of his own, the impetus slackened and stopped, the wells of sweet water were

dry

and the cisterns were broken. These promising oases that flourish among monotonous

humanity dry up so quickly, most of them. They are verdant to us but a night. There

are so

few minds that are fitted to race side by side, to wrestle and rejoice together, even

unto

the paean. And after all that is the base of affinities, that mental brotherhood.

The

glamour of every other passion and enthusiasm fades like the brilliance of an afterglow,

leaving shadow and chill and a nameless ennui.

One evening Buchanan stopped the Count in the hall.

"May I trouble you for a moment, sir? A friend of mine who is something of a bibliomaniac has sent me from Munich a copy of Rabelais stamped with the Bavarian arms. There is an autograph on the fly leaf, indeed, two of them, and he suspects that one of them may be Ludwig's."

The Count adjusted his eye glasses and looked thoughtfully at the faded writing: "Lola M.," and further down the page, "Ludwig." "You have certainly every reason for such a supposition. Ludwig was one of the few monarchs who really cared enough for books to put his name and in one Lola Montes' name, too, for that matter. However, in these autographs one can never tell. If you will step upstairs with me we can soon assure ourselves."

"O, I did not mean to trouble you; you were just going out, were you not?"

"It was nothing of importance, nothing that I would not gladly abandon for the prospect of your company."

Buchanan followed him up the stuffy stairway and down the narrow hall. He was conscious of a subdued thrill of quickened curiosity upon entering the Count's apartments. But as his host lit the gas one covert glance about him told him that he need not exercise rigid surveillance over his eyes. Beyond a number of books and pictures, portraits, most of them, there was little to distinguish the room from the ordinary furnished apartment. There was the usual faded moquette carpet, the same cheap rugs and the inevitable shiny oak furniture. The silver fittings of the writing table, engraved with a crest and monogram, were the only suggestions of the rank of the occupant.

"Be seated there, on the divan, and I will find a signature I know to be authentic. We will compare them." As he spoke he tugged at the unwilling drawers of a chiffonier in the corner.

"This furniture," he remarked apologetically, "partakes somewhat of the sullen nature of the house. There, we have it at last."

He lifted from the drawer a small steel chest and placed it upon the table. After opening it with a key attached to his watchguard, he drew out a pile of papers and began sorting them. Buchanan watched curiously the various documents as they passed through his hands. Some of them were on parchment and suggested venerable histories, some of them were encased in modern envelopes, and some were on tinted note paper with heavily embossed monograms, suggesting histories equally alluring if less venerable. If those notes could speak the import of their contents, what a roar of guttural bassos, soaring sopranos, and impassioned contraltos and tenors there would be! And would the dominant note of the chorus be of Ares or Eros, he wondered?

He was aroused from his speculations by the Count's slight exclamation when he found the paper he was hunting for. He unfolded a stiff sheet of note paper, and then folding it back so that only the signature was visible, sat down beside his guest. The signature, "Ludwig W.," stood out clearly from the paper he held.

"Not Ludwig's, evidently," said the Count, "now we will look as to the other. I am sorry to say we have that, too."

He opened the other paper he held, and folded it as he had done the first. The signature in this case was simply "Lola."

"They seem to be identical. I fancied as much. It was Madame Montes' custom to take whatever she wanted from the royal library and she seldom troubled herself to return it. The second name is only another evidence of her inordinate vanity, and they are too numerous to be of especial interest. I must apologize for showing you the signatures in this singularly unsatisfactory manner, but the contents of these communications were strictly personal, and, of course, were not addressed to me. I remember very little of the reign of the first Ludwig myself. There are a number of names among those papers that might inter- est you, if you care to see them and will omit the body of the documents. They are, many of them, papers that should never have been written at all. Such things are inevitable in very old families, though I could never understand their motive for preserving them. There is only one way to handle such things, and that is with absolute and unvarying care. To show them even to an appreciative friend is a form of blackmail. I dislike the responsibility of knowing their contents myself. I have not read any of them for years."

"And yet you, too, keep them?"

"Certainly, inbred tradition, I suppose. I have often intended to destroy them, but I have always deferred the actual doing of it. Since they have enabled me to be of some service to you, I am glad I have delayed the holocaust."

The conventional ring of the last remark seemed to politely close all further serious discussion of the subject. Buchanan checked the question he had already mentally uttered, and taking a chair by the table, looked at the signatures his host selected. They were names that consumed him with an overwhelming curiosity and made his ears tingle and his checks burn; single names, most of them, those single names that Balzac said made the observer dream. As the Count took another package of documents from the box his fingers caught a small gold chain attached to some metallic object that rang sharply against the sides of the box as he lifted his hand.

"The iron cross!" cried Buchanan involuntarily, with a quick inward breath.

"Yes, it is one that I won on the field of Gravelotte years ago. It is my only contribution to this box. I have been a very ordinary man, Mr. Buchanan. In families like ours there must be some men who neither make nor break, but try to keep things together. That my efforts in that direction were somewhat futile was not entirely my fault. I had two brothers who bore the title before me; they were both talented men, and when my turn came there was very little left to save."

"I fancied you had been more of a student than a man of affairs."

"Student is too grave a word. I have always read; at one time I thought that of itself gave one a sufficient purpose, but like other things it fails one at last, at least the living interest of it. At present I am only a survivor. Here, where every one plays for some stake, I realize how nearly extinct is the class to which I belong, and that I am a sort of survival of the unfit, with no duty but to keep an escutcheon that is only a name and a sword that the world no longer needs. An old pagan back in Julian's time who still clung to a despoiled Olympus and a vain philosophy, dead as its own abstruse syllogisms, might have felt as I do when the new faith, throbbing with potentialities, was coming in. The life of my own father seems to be as far away as the lives of the ancient emperors. It is not a pleasant thing to be the last of one's kind. The tedium vitae descends heavily upon one."

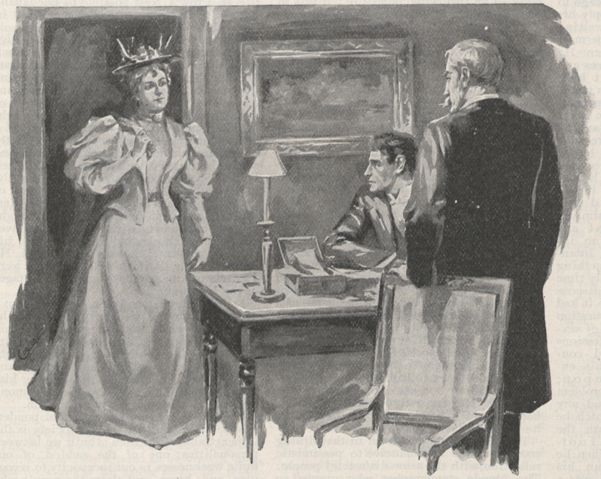

As the Count was speaking, they heard a ripple of loud laughter on the stairs and a rustle of draperies in the hall, and a tall blonde woman, dressed in a tight fitting tailor-made gown, with a pair of long lavender gloves lying jauntily over her shoulder, entered and bowed graciously to the Count.

"Bon soir, mon père, I was not aware you had company." There was in her voice that peculiarly hard throat tone that stage people so often use in conversation.

"Mr. Buchanan, my daughter, Helena."

Buchanan bowed and muttered a greeting, uncertain by just what title he should address her.

"No Countess, if you please, Mr. Buchanan. Just plain Helena De Koch. Titles are out of date, and more than absurd in our case. I come from a rehearsal of a concert where I sing for money, attired in a ready-made gown, botched over by a tailor, to visit my respected parent in a fourth-rate lodging house, and you call me Countess! Could anything be more innately funny? Titles only go in comic opera now. I have often tried to persuade my father to content himself with Paul De Koch."

The Count smiled. "My name was not mine to make, Helena, and I am not at all ashamed of it."

The young lady's keen but rather indifferent eyes had dwelt on Buchanan but a moment, but he felt as though he had been inspected by a drill sergeant, and that no detail of his person or attire had escaped her.

She glanced at the table and then at the Count. "So you have decided to become practical at last?"

A shade of extreme annoyance swept quickly over the Count's face. He replied stiffly.

"I have merely been showing Mr. Buchanan an autograph he wished to see."

"O, so that is all! I might have known it. People do not recover from a mania in a day." She laughed rather unpleasantly and turned graciously to Buchanan. "Have you persuaded him to show you any of them? The contents are much more interesting than the autographs, rather side lights on history, you know." Her eyelid drooped a little with an insinuating glance, just enough to suggest a wink that did not come to pass, but he felt strangely repelled by even the suggestion. It must have been the connection that made it so objectionable, he reflected. She seemed to cheapen the Count and all his surroundings.

"No, my interest goes no further than the autographs."

"A polite prevarication I imagine. You will have to get more in the shadow if you hide the curiosity in your eyes. I don't blame you, he found me reading them once, and all the old Koch temper came out. I never knew he had it until then. Our tempers and our title are the only remnants of our former glory. The one is quite as ridiculous as the other, since we have no one to get angry at but each other. Poverty has no right to indignation at all. I speak respectfully even to a cabman. Papa shows his superiority by having no cabman at all."

"I think neither of you need do anything at all to show that," said Buchanan, politely.

"O, come, you are all like impressarios, you Americans, and the further West one goes the worse it is. I never saw a manager who could resist a title; I only use mine on such occasions."

Buchanan saw that his host looked ill at ease, so he endeavored to change the subject.

"You sing, I believe?"

"O, yes, in oratorio and concert. Cher papa will not hear of the opera. Oratorio seems to be the special retreat of decayed gentility. I don't believe in those distinctions myself; I have found that a title dating from the foundation of the Empire does not buy one a spring bonnet, and that one of the oldest names in Europe will not keep one in gloves. One of your clever Frenchmen said there is nothing in the world but money, the gallows excepted. But His Excellency here never quotes that. Papa is an aristocrat, while I am bourgeoise to the tips of my fingers." She waved her highly polished nails toward Buchanan.

He thought that she could not have summarized herself better. The instinctive dislike he had always felt for her had been steadily growing into an aversion since she entered the room. It was by no means the first time he had seen her, she was almost a familiar figure about the boarding house, and often came to dine with the Count. Her florid coloring and elaborately blonde hair might have been said to be a general expression of her style. Under that yellow bang was a low straight forehead, and straight brows from behind which looked out a pair of blue eyes, large and full but utterly without depth, and cold as icicles, which seemed to be continually estimating the pecuniary value of the world. The cheeks were full and the chill decided in spite of its dimple. The upper lip was full and short and the nostril spare. They were scarcely the features one would expect to find in the descendant of an ancient house, seeming more accidental than formed by any perpetuated tendencies of blood. Her hands were broad and plump like her wrists.

Mademoiselle was on almost familiar terms with the landlady of Crow's Nest, and Buchanan fancied that she was responsible for the bits of gossip concerning the Count that floated about the house and were daily rehearsed by the languid widow. The widow had gone so far as to darkly express her doubts as to this effulgent blonde being the Count's daughter at all, and Buchanan had been guilty of rather hoping that she was right. It would be rather less of a reflection on the Count, he thought. But to-night's conversation left him no room for doubt, and in watching the contrast between her full, florid countenance and the chastened face across the table, he wondered if the materialists of this world were always hale and full-fed, while the idealists were pale and gray as the shadows that kept them company. But one did not find time to muse much about anything in Mademoiselle De Koch's presence.

"By the way, cher papa, you are coming to-morrow night to hear me sing that waltz song of Arditti's?"

"Certainly, if you wish, but I am not fond of that style of music."

"O, certainly not, that's not to be expected or hoped for, nothing but mossbacks. But, seriously, one cannot sing Mendelssohn or Haydn forever, and all the modern classics are so abominably difficult," said Mademoiselle, beginning to draw on her gloves, which Buchanan noticed were several sizes too small and required a great deal of coaxing. Indeed everything that Mademoiselle wore fit her closely. She was of that peculiar type of blonde loveliness which impresses one as being always on the verge of embonpoint, and its possessor seems always to be in a state of nervous apprehension lest she should cross the dead line and openly and fearlessly be called stout.

At this juncture a gentle knock was heard at the door, and Mademoiselle remarked carelessly, "That's only Tony. Come in!"

A gentleman entered and bowed humbly to Mademoiselle. He was a little tenor whom Buchanan remembered having seen before, and whose mild dark eyes and swarthy skin had given him a pretext to adopt an Italian stage name. He was a slight, narrow chested man and a receding chin and a generally "professional" and foreign air which was unmistakably cultivated.

"A charming evening, Count. Chicago weather is so seldom genial in the winter."

After presenting him to Buchanan the Count answered him, "I have not been out, but it seems so here."

"Doubtless, in Mademoiselle's society. But you are busy?"

He glanced inquiringly at Mademoiselle. Buchanan fancied that the question was addressed to her rather than to the Count, and thought he intercepted an answering glance.

"Not at all, we were merely amusing ourselves. Must you leave us already?"

"I think Mademoiselle has another rehearsal. You know what it means to presume to keep pace with an art, eternal vigilance. There is no rest for the weary in our profession—not, at least, in this world." This was said with a weighty sincerity that almost provoked a smile from Buchanan. There are two words which no Chicago singer can talk ten minutes without using: "art" and "Chicago," and this gentleman had already indulged in both.

"O, yes, we must be gone to practice the despised Arditti. Come to-morrow night if you can. Tony here will give you tickets. And if Mr. Buchanan should have nothing better to do, pray bring him with you."

Buchanan assured her that he could have nothing more agreeable at any rate, and would be delighted to go. She took possession of the tenor and departed.

( To Be Concluded in the October Number .)