Collier's

From Collier's, 49 (May 18, 1912): 16-17; 41.

Behind the Singer Tower

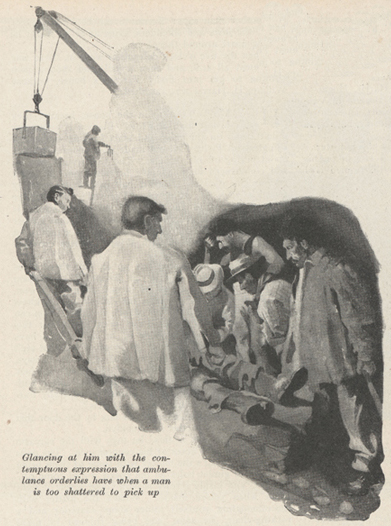

ILLUSTRATED BY GEORGE HARDING Glancing at him with the contemptuous expression that ambulance orderlies have when

a man is too shattered to pick up

Glancing at him with the contemptuous expression that ambulance orderlies have when

a man is too shattered to pick up

IT WAS a hot, close night in May, the night after the burning of the Mont Blanc Hotel, and some half dozen of us who had been thrown together, more or less, during that terrible day, accepted Fred Hallet's invitation to go for a turn in his launch, which was tied up in the North River. We were all tired and unstrung and heartsick, and the quiet of the night and the coolness on the water relaxed our tense nerves a little. None of us talked much as we slid down the river and out into the bay. We were in a kind of stupor. When the launch ran out into the harbor, we saw an Atlantic liner come steaming up the big sea road. She passed so near us that we could see her crowded steerage decks.

"It's the Re di Napoli," said Johnson of the "Herald." "She's going to land her first cabin passengers to-night, evidently. Those people are terribly proud of their new docks in the North River; feel they've come up in the world."

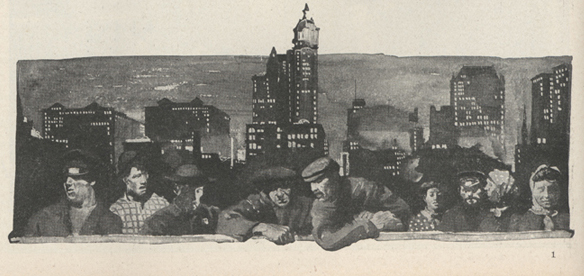

We ruffled easily along through the bay, looking behind us at the wide circle of lights that rim the horizon from east to west and from west to east, all the way round except for that narrow, much-traveled highway, the road to the open sea. Running a launch about the harbor at night is a good deal like bicycling among the motors on Fifth Avenue. That night there was probably no less activity than usual; the turtle-backed ferryboats swung to and fro, the tugs screamed and panted beside the freight cars they were towing on barges, the Coney Island boats threw out their streams of light and faded away. Boats of every shape and purpose went about their business and made noise enough as they did it, doubtless. But to us, after what we had been seeing and hearing all day long, the place seemed unnaturally quiet and the night unnaturally black. There was a brooding mournfulness over the harbor, as if the ghost of helplessness and terror were abroad in the darkness. One felt a solemnity in the misty spring sky where only a few stars shone, pale and far apart, and in the sighs of the heavy black water that rolled up into the light. The city itself, as we looked back at it, seemed enveloped in a tragic self-consciousness. Those incredible towers of stone and steel seemed, in the mist, to be grouped confusedly together, as if they were confronting each other with a question. They looked positively lonely, like the great trees left after a forest is cut away. One might fancy that the city was protesting, was asserting its helplessness, its irresponsibility for its physical conformation, for the direction it had taken. It was an irregular parallelogram pressed between two hemispheres, and, like any other solid squeezed in a vise, it shot upward.

THERE were six of us in the launch: two newspapermen—Johnson and myself; Fred Hallet, the engineer, and one of his draftsmen; a lawyer from the District Attorney's office; and Zablowski, a young Jewish doctor from the Rockefeller Institute. We did not talk; there was only one thing to talk about, and we had had enough of that. Before we left town the death list of the Mont Blanc had gone above three hundred.

The Mont Blanc was the complete expression of the New York idea in architecture; a thirty-five story hotel which made the Plaza look modest. Its prices, like its proportions, as the newspapers had so often asseverated, outscaled everything in the known world. And it was still standing there, massive and brutally unconcerned, only a little blackened about its thousand windows and with the foolish fire escapes in its court melted down. About the fire itself nobody knew much. It had begun on the twelfth story, broken out through the windows, shot up long streamers that had gone in at the windows above, and so on up to the top. A high wind and much upholstery and oiled wood had given it incredible speed.

On the night of the fire the hotel was full of people from everywhere, and by morning half a dozen trusts had lost their presidents, two States had lost their Governors, and one of the great European powers had lost its Ambassador. So many businesses had been disorganized that Wall Street had shut down for the day. They had been snuffed out, these important men, as lightly as the casual guests who had come to town to spend money, or as the pampered opera singers who had returned from an overland tour and were waiting to sail on Saturday. The lists were still vague, for whether the victims had jumped or not, identification was difficult, and, in either case, they had met with obliteration, absolute effacement, as when a drop of water falls into the sea.

OUT of all I had seen that day, one thing kept recurring to me; perhaps because it was so little in the face of a destruction so vast. In the afternoon, when I was going over the building with the firemen, I found on the ledge of a window on the fifteenth floor, a man's hand snapped off at the wrist as cleanly as if it had been taken off by a cutlass—he had thrown out his arm in falling.

It had belonged to Graziani, the tenor, who had occupied a suite on the thirty-second floor. We identified it by a little-finger ring, which had been given to him by the German Emperor. Yes, it was the same hand. I had seen it often enough when he placed it so confidently over his chest as he began his "Celeste Aida," or when he lifted—much too often, alas!—his little glasses of white arrack at Martin's. When he toured the world he must have whatever was most costly and most characteristic in every city; in New York he had the thirty-second floor, poor fellow! He had plunged from there toward the cobwebby life nets stretched five hundred feet below on the asphalt. Well, at any rate, he would never drag out an obese old age in the English country house he had built near Naples.

Heretofore fires in fireproof buildings of many stories had occurred only in factory lofts, and the people who perished in them, fur workers and garment workers, were obscure for more reasons than one; most of them bore names unpronounceable to the American tongue; many of them had no kinsmen, no history, no record anywhere.

But we realized that, after the burning of the Mont Blanc, the New York idea would be called to account by every state in the Union, by all the great capitals of the world. Never before, in a single day, had so many of the names that feed and furnish the newspapers appeared in their columns all together, and for the last time.

IN NEW YORK the matter of height was spoken of jocularly and triumphantly. The very window cleaners always joked about it as they buckled themselves fast outside your office in the forty-fifth story of the Wertheimer tower, though the average for window cleaners, who, for one reason or another, dropped to the pavement was something over one a day. In a city with so many millions of windows that was not perhaps an unreasonable percentage. But we felt that the Mont Blanc disaster would bring our particular type of building into unpleasant prominence, as the cholera used to make Naples and the conditions of life there too much a matter of discussion, or as the earthquake of 1905 gave such undesirable notoriety to the affairs of San Francisco.

For once we were actually afraid of being too much in the public eye, of being overadvertised. As I looked at the great incandescent signs along the Jersey shore, blazing across the night the names of beer and perfumes and corsets, it occurred to me that, after all, that kind of thing could be overdone; a single name, a single question, could be blazed too far. Our whole scheme of life and progress and profit was perpendicular.

There was nothing for us but height. We were whipped up the ladder. We depended upon the ever-growing possibilities of girders and rivets as Holland depends on her dikes.

"Did you ever notice," Johnson remarked when we were about halfway across to Staten Island, "what a Jewy-looking thing the Singer Tower is when it's lit up? The fellow who placed those incandescents must have had a sense of humor. It's exactly like the Jewish high priest in the old Bible dictionaries."

He pointed back, outlining with his forefinger the jeweled miter, the high, sloping shoulders, and the hands pressed together in the traditional posture of prayer.

Zablowski, the young Jewish doctor, smiled and shook his head. He was a very handsome fellow, with sad, thoughtful eyes, and we were all fond of him, especially Hallet, who was always teasing him. "No, it's not Semitic, Johnson," he said. "That high-peaked turban is more apt to be Persian. He's a Magi or a fire-worshiper of some sort, your high priest. When you get nearer he looks like a Buddha, with two bright rings in his ears."

ZABLOWSKI pointed with his cigar toward the blurred Babylonian heights crowding each other on the narrow tip of the island. Among them rose the colossal figure of the Singer Tower, watching over the city and the harbor like a presiding Genius. He had come out of Asia quietly in the night, no one knew just when or how, and the Statue of Liberty, holding her feeble taper in the gloom off to our left, was but an archeological survival.

"Who could have foreseen that she, in her high-mindedness, would ever spawn a great heathen idol like that?" Hallet exclaimed. "But that's what idealism comes to in the end, Zablowski."

Zablowski laughed mournfully. "What did you expect, Hallet? You've used us for your ends—waste for your machine, and now you talk about infection. Of course we brought germs from over there," he nodded toward the northeast.

"Well, you're all here, at any rate, and I won't argue with you about all that to-night," said Hallet wearily. "The fact is," he went on as he lit a cigar and settled deeper into his chair, "when we met the Re di Napoli back there, she set me thinking. She recalled something that happened when I was a boy just out of Tech; when I was working under Merryweather on the Mont Blanc foundation."

WE ALL looked up. Stanley Merryweather was the most successful manipulator of structural steel in New York, and Hallet was the most intelligent; the enmity between them was one of the legends of the Engineers' Society.

Hallet saw our interest and smiled. "I suppose you've heard yarns about why Merryweather and I don't even pretend to get on. People say we went to school together and then had a terrible row of some sort. The fact is, we never did get on, and back there in the foundation work of the Mont Blanc our ways definitely parted. You know how Merryweather happened to get going? He was the only nephew of old Hughie Macfarlane, and Macfarlane was the pioneer in steel construction. He dreamed the dream. When he was a lad working for the Pennsylvania Bridge Company, he saw Manhattan just as it towers there to-night. Well, Macfarlane was aging and he had no children, so he took his sister's son to make an engineer of him. Macfarlane was a thoroughgoing Scotch Presbyterian, sound Pittsburgh stock, but his sister had committed an indiscretion. She had married a professor of languages in a theological seminary out there; a professor who knew too much about some Oriental tongues I needn't name to be altogether safe. It didn't show much in the old professor, who looked like a Baptist preacher except for his short, thick hands, and of course it is very much veiled in Stanley. When he came up to the Massachusetts Tech he was a big, handsome boy, but there was something in his moist, bright blue eye—well, something that you would recognize, Zablowski."

Zablowski chuckled and inclined his head delicately forward.

Haller continued: "Yes, in Stanley Merryweather there were racial characteristics. He was handsome and jolly and glitteringly frank and almost insultingly cordial, and yet he was never really popular. He was quick and superficial, built for high speed and a light load. He liked to come it over people, but when you had him, he always crawled. Didn't seem to hurt him one bit to back down. If you made a fool of him to-night—well, 'tomorrow's another day,' he'd say lightly, and to-morrow he'd blossom out in a new suit of clothes and a necktie of some unusual weave and haunting color. He had the feeling for color and texture. The worst of it was that, as truly as I'm sitting here, he never bore a grudge toward the fellow who'd called his bluff and shown him up for a lush growth; no ill feeling at all, Zablowski. He simply didn't know what that meant—"

HALLET'S sentence trailed and hung wistfully in the air, while Zablowski put his hand penitently to his forehead.

"Well, Merryweather was quick and he had plenty of spurt and a taking manner, and he didn't know there had ever been such a thing as modesty or reverence in the world. He got all round the old man, and old Mac was perfectly foolish about him. It was always: 'Is it well with the young man Absalom?' Stanley was a year ahead of me in school, and when he came out of Tech the old man took him right into the business. He married a burgeoning Jewish beauty, Fanny Reizenstein, the daughter of the importer, and he hung her with the jewels of the East until she looked like the Song of Solomon done into motion pictures. I will say for Stanley that he never pretended that anything stronger than Botticelli hurt his eyes. He opened like a lotus flower to the sun and made a streak of color, even in New York. Stanley always felt that Boston hadn't done well by him, and he enjoyed throwing jobs to old Tech men. 'Largess, largess, Lord Marmion, all as he lighted down.' When they began breaking ground for the Mont Blanc I applied for a job because I wanted experience in deep foundation work. Stanley beamed at me across his mirror-finish mahogany and offered me something better, but it was foundation work I wanted, so early in the spring I went into the hole with a gang of twenty dagos.

"It was an awful summer, the worst New York can do in the way of heat, and I guess that's the worst in the world, excepting India maybe. We sweated away, I and my twenty dagos, and I learned a good deal—more than I ever meant to. Now there was one of those men I liked, and it's about him I must tell you. His name was Cæsaro, but he was so little that the other dagos in the hole called him Cæsarino, Little Cæsar. He was from the island of Ischia, and I had been there when a young lad with my sister who was ill. I knew the particular goat track Cæsarino hailed from, and maybe I had seen him there among all the swarms of eager, panting little animals that roll around in the dust and somehow worry through famine and fever and earthquake, with such a curiously hot spark of life in them and such delight in being allowed to live at all.

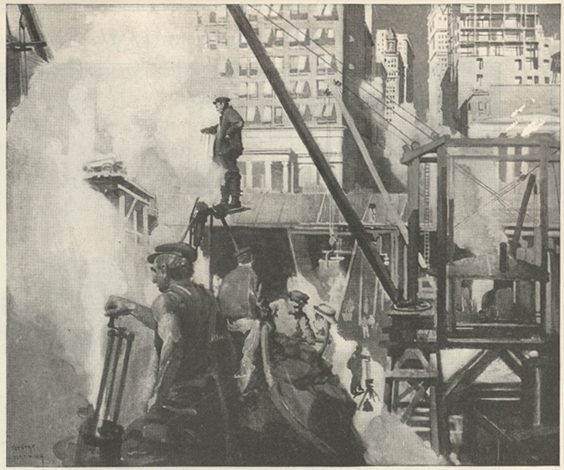

All this time we were making things move in the hole

All this time we were making things move in the hole

"Cæsarino's father was dead and his older brother was married and had a little swarm of his own to look out for. Cæsarino and the next two boys were coral divers and went out with the fleet twice a year; when they were at home they worked about by the day in the vineyards. He couldn't remember ever having had any clothes on in summer until he was ten; spent all his time swimming and diving and sprawling about among the nets on the beach. I've seen 'em, those wild little water dogs; look like little seals with their round eyes and their hair always dripping. Cæsarino thought he could make more money in New York than he made diving for coral, and he was the mainstay of the family. There were ever so many little water dogs after him; his father had done the best he could to insure the perpetuity of his breed before he went under the lava to begin all over again by helping to make the vines grow in that marvelously fruitful volcanic soil. Little Cæsar came to New York, and that is where we begin.

"He was one of the twenty crumpled, broken little men who worked with me down in that big hole. I first noticed him because he was so young, and so eager to please, and because he was so especially frightened. Wouldn't you be at all this terrifying, complicated machinery, after sun and happy nakedness and a goat track on a volcanic island, with the same old water always rolling in and in? Haven't you ever noticed how, when a dago is hurt on the railroad and they trundle him into the station on a truck, another dago always runs alongside him, holding his hand and looking the more scared of the two? Little Cæsar ran about the hole looking like that. He was afraid of everything he touched. He never knew what might go off. Suppose we went to work for some great and powerful nation in Asia that had a civilization built on sciences we knew nothing of, as ours is built on physics and chemistry and higher mathematics; and suppose we knew that to these people we were absolutely meaningless as social beings, were waste to clean their engines as Zablowski says; that we were there to do the dangerous work, to be poisoned in caissons under rivers, blown up by blasts, drowned in coal mines, and that these masters of ours were as indifferent to us individually as the Carthaginians were to their mercenaries? I'll tell you we'd guard the precious little spark of life with trembling hands."

"But I say—" sputtered the lawyer from the District Attorney's office.

"I know, I know, Chambers." Hallet put out a soothing hand. "We don't want 'em, God knows. They come. But why do they come? It's the pressure of their time and ours. It's not rich pickings they've got where I've worked with them, let me tell you. Well, Cæsarino, with the others, came. The first morning I went on my job he was there, more scared of a new boss than any of the others; literally quaking. He was only twenty-three and lighter than the other men, and he was afraid I'd notice that. I thought he would pull his shoulder blades loose. After one big heave I stopped beside him and dropped a word: 'buono soldato.' In a moment he was grinning with all his teeth, and he squeaked out: ' Buono soldato, da boss he talka dago!'That was the beginning of our acquaintance."

Hallet paused a moment and smoked thoughtfully. He was a soft man for the iron age, I reflected, and it was easy enough to see why Stanley Merryweather had beaten him in the race. There is a string to every big contract in New York, and Hallet was always tripping over the string.

"From that time on we were friends. I knew just six words of Italian, but that summer I got so that I could understand his fool dialect pretty well. I used to feel ashamed of the way he'd look at me, like a girl in love. You see, I was the only thing he wasn't afraid of. On Sundays we used to poke off to a beach somewhere, and he'd lie in the water all day and tell me about the coral divers and the bottom of the Mediterranean. I got very fond of him. It was my first summer in New York and I was lonesome, too. The game down here looked pretty ugly to me. There were plenty of disagreeable things to think about, and it was better fun to see how much soda water Cæsarino could drink. He never drank wine. He used to say: 'At home—oh, yes-a! At New York,' making that wise little gesture with the forefinger between his eyes, 'niente. Sav'-a da mon'.' But even his economy had its weak spots. He was very fond of candy, and he was always buying 'pop-a corn off-a da push-a cart.'

"However, he had sent home a good deal of money, and his mother was ailing and he was so frightened about her and so generally homesick that I urged him to go back to Ischia for the winter. There was a poor prospect for steady work, and if he went home he wouldn't be out much more than if he stayed in New York working on half time. He backed and filled and agonized a good deal, but when I at last got him to the point of engaging his passage he was the happiest dago on Manhattan Island. He told me about it all a hundred times.

"His mother, from the piccola casa on the cliff, could see all the boats go by to Naples. She always watched for them. Possibly he would be able to see her from the steamer, or at least the casa, or certainly the place where the casa stood.

"ALL this time we were making things move in the hole. Old Macfarlane wasn't around much in those days. He passed on the results, but Stanley had a free hand as to ways and means. He made amazing mistakes, harrowing blunders. His path was strewn with hairbreadth escapes, but they never dampened his courage or took the spurt out of him. After a close shave he'd simply duck his head and smile brightly and say: 'Well, I got that across, old Persimmons!' I'm not underestimating the value of dash and intrepidity. He made the wheels go round. One of his maxims was that men are cheaper than machinery. He smashed up a lot of hands, but he always got out under the fellow-servant act. 'Never been caught yet, huh?' he used to say with his pleasant, confiding wink. I'd been complaining to him for a long while about the cabling, but he always put me off; sometimes with a surly insinuation that I was nervous about my own head, but oftener with fine good humor. At last something did happen in the hole.

"It happened one night late in August, after a stretch of heat that broke the

thermometers. For a week there

(Continued on page 41)

Behind the Singer Tower

(Concluded from page 17)

hadn't been a dry human being in New York. Your linen went down three minutes after

you put it

on. We moved about insulated in moisture, like the fishes in the sea. That night I

couldn't

go down into the hole right away. When you once got down there the heat from the boilers

and

the steam from the diamond drills made a temperature that was beyond anything the

human frame

was meant to endure. I stood looking down for a long while, I remember. It was a hole

nearly

three acres square, and on one side the Savoyard rose up twenty stories, a straight

blank, brick

wall. You know what a mess such a hole is; great boulders of rock and deep pits of

sand and gulleys

of water, with drills puffing everywhere and little crumpled men crawling about like

tumble bugs

under the stream from the searchlight. When you got down into the hole, the wall of

the

Savoyard seemed to go clear up to the sky; that pale blue, enamel sky of a New York

midsummer

night. Six of my men were moving a diamond drill and settling it into a new place,

when

one of the big clamshells that swung back and forth over the hole fell with its load

of

sand—the worn cabling, of course. It was directly over my men when it fell. They

couldn't hear anything for the noise of the drill; didn't know anything had happened

until

it struck them. They were bending over, huddled together, and the thing came down

on them

like a brick dropped on an ant hill. They were all buried, Cæsarino among them. When

we

got them out, two were dead and the others were dying. My boy was the first we reached.

The edge of the clamshell had struck him, and he was all broken to pieces. The moment

we

got his head out he began chattering like a monkey. I put my ear down to his lips—the

other drills were still going—and he was talking about what I had forgotten, that

his

steamer ticket was in his pocket and that he was to sail next Saturday. 'E necessario, signore, é necessario,' he kept repeating. He had

written his family what boat he was coming on, and his mother would be at the door,

watching

it when it went by to Naples. 'E necessario, signore, é

necessario.'

"WHEN the ambulances got there the orderlies lifted two of the men and had them carried up to the street, but when they turned to Cæsarino they dismissed him with a shrug, glancing at him with the contemptuous expression that ambulance orderlies come to have when they see that a man is too much shattered to pick up. He saw the look, and a boy who doesn't know the language learns to read looks. He broke into sobs and began to beat the rock with his hands. 'Curs-a da hole, curs-a da hole, curs-a da build'!' he screamed, bruising his fists on the shale. I caught his hands and leaned over him. 'Buono soldato, buono soldato,' I said in his ear. His shrieks stopped, and his sobs quivered down. He looked at me—' Buono soldato,' he whispered, 'ma, perche?' Then the hemorrhage from his mouth shut him off, and he began to choke. In a few minutes it was all over with Little Cæsar.

"About that time Merryweather showed up. Some one had telephoned him, and he had come down in his car. He was a little frightened and pleasurably excited. He has the truly journalistic mind—saving your presence, gentlemen—and he likes anything that bites on the tongue. He looked things over and ducked his head and grinned good-naturedly. 'Well, I guess you've got your new cabling out of me now, huh, Freddy?' he said to me. I went up to the car with him. His hand shook a little as he shielded a match to light his cigarette. 'Don't get shaky, Freddy. That wasn't so worse,' he said, as he stepped into his car.

"For the next few days I was busy seeing that the boy didn't get buried in a trench with a brass tag around his neck. On Saturday night I got his pay envelope, and he was paid for only half of the night he was killed; the accident happened about eleven o'clock. I didn't fool with any paymaster. On Monday morning I went straight to Merryweather's office, stormed his bower of rose and gold, and put that envelope on the mahogany between us. 'Merryweather,' said I, 'this is going to cost you something. I hear the relatives of the other fellows have all signed off for a few hundred, but this little dago hadn't any relatives here, and he's going to have the best lawyers in New York to prosecute his claim for him.'

"Stanley flew into one of his quick tempers. 'What business is it of yours, and what are you out to do us for?'

"'I'm out to get every cent that's coming to this boy's family.'

"'How in hell is that any concern of yours?'

"'Never mind that. But we've got one awfully good case, Stanley. I happen to be the man who reported to you on that cabling again and again. I have a copy of the letter I wrote you about it when you were at Mount Desert, and I have your reply.'

"STANLEY whirled around in his swivel chair and reached for his checkbook. 'How much are you gouging for?' he asked with his baronical pout.

"'Just all the courts will give me. I want it settled there,' I said, and I got up to go.

"'Well, you've chosen your class, sir,' he broke out, ruffling up red. 'You can stay in a hole with the guineas till the end of time for all of me. That's where you've put yourself.'

"I got my money out of that concern and sent it off to the old woman in Ischia, and that's the end of the story. You all know Merryweather. He's the first man in my business since his uncle died, but we manage to keep clear of each other. The Mont Blanc was a milestone for me; one road ended there and another began. It was only a little accident, such as happens in New York every day in the year, but that one happened near me. There's a lot of waste about building a city. Usually the destruction all goes on in the cellar; it's only when it hits high, as it did last night, that it sets us thinking. Wherever there is the greatest output of energy, wherever the blind human race is exerting itself most furiously, there's bound to be tumult and disaster. Here we are, six men, with our pitiful few years to live and our one little chance for happiness, throwing everything we have into that conflagration on Manhattan Island, helping, with every nerve in us, with everything our brain cells can generate, with our very creature heat, to swell its glare, its noise, its luxury, and its power. Why do we do it? And why, in heaven's name, do they do it? Ma, perche? as Cæsarino said that night in the hole. Why did he, from that lazy volcanic island, so tiny, so forgotten, where life is simple and pellucid and tranquil, shaping itself to tradition and ancestral manners as water shapes itself to the jar, why did he come so far to cast his little spark into the bonfire? And the thousands like him, from islands even smaller and more remote, why do they come, like iron dust to the magnet, like moths to the flame? There must be something wonderful coming. When the frenzy is over, when the furnace has cooled, what marvel will be left on Manhattan Island?"

"What has been left often enough before," said Zablowski dreamily. "What was left in India, only not half so much."

Hallet disregarded him. "What it will be is a new idea of some sort. That's all that ever comes, really. That's what we are all the slaves of, though we don't know it. It's the whip that cracks over us till we drop. Even Merryweather—and that's where the gods have the laugh on him—every firm he crushes to the wall, every deal he puts through, every cocktail he pours down his throat, he does it in the service of this unborn Idea, that he will never know anything about. Some day it will dawn, serene and clear, and your Moloch on the Singer Tower over there will get down and do it Asian obeisance."

WE reflected upon this while the launch, returning toward the city, ruffled through the dark furrows of water that kept rolling up into the light. Johnson looked back at the black sea road and said quietly:

"Well, anyhow, we are the people who are doing it, and whatever it is, it will be ours."

Hallet laughed. "Don't call anything ours, Johnson, while Zablowski is around."

"Zablowski," Johnson said irritably, "why don't you ever hit back?"