Woman's Home Companion

From Woman's Home Companion, 52 (February 1925): 7-9, 86, 89-90.

Uncle Valentine

(Adagio non troppo)

"Oh don't look so frightened," he said irritably, "and don't send

the girls away"

ILLUSTRATED BY FRANCES ROGERS

A Novelette in Two Parts

"Oh don't look so frightened," he said irritably, "and don't send

the girls away"

ILLUSTRATED BY FRANCES ROGERS

A Novelette in Two Parts

One morning not long ago I heard Louise Ireland give a singing lesson to a young countrywoman of mine, in her studio in Paris. Ireland must be quite sixty now, but there is not a break in the proud profile; she is still beautiful, still the joy of men, young and old. To hear her give a lesson is to hear a fine performance. The pupil was a girl of exceptional talent, handsome and intelligent, but she had the characteristic deficiency of her generation she found nothing remarkable. She realized that she was fortunate to get in a few lessons with Ireland, but good fortune was what she expected, and she probably thought Ireland didn't every day find such good material to work with.

When the vocal lesson was over the girl said, "May I try that song you told me to look at?"

"If you wish. Have you done anything with it?"

"I've worked on it a little." The young woman unstrapped a roll of music. "I've tried over most of the songs in this book. I'm crazy about them. I never heard of Valentine Ramsay before."

"Sad for him," murmured the teacher.

"Was he English?"

"No, American, like you," sarcastically.

"I went back to the shop for more of his things, but they had only this one collection. Didn't he do any others?"

"A few. But these are the best."

"But I don't understand. If he could do things like these, why didn't he keep it up? What prevented him?"

"Oh, the things that always prevent one: marriage, money, friends, the general social order. Finally a motor truck prevented him, one of the first in Paris. He was struck and killed one night, just out of the window there, as he was going on to the Pont Royal. He was barely thirty."

The girl said "Oh!" in a subdued voice, and actually crossed the room to look out of the window.

"If you wish to know anything further about him, this American lady can tell you. She knew him in his own country. Now I'll see what you've done with that." Ireland shook her loose sleeves back from her white arms and began to play the song:

I know a wall where red roses grow…I

The fine line of hills,

clad with forest, that rose

above a historical American river

The fine line of hills,

clad with forest, that rose

above a historical American river

Yes, I had known Valentine Ramsay. I knew him in a lovely place, at a lovely time, in a bygone period of American life; just at the incoming of this century which has made all the world so different.

I was a girl of sixteen, living with my aunt and uncle at Fox Hill, in Greenacre. My mother and father had died young, leaving me and my little sister, Betty Jane, with scant provision for our future. Aunt Charlotte and Uncle Harry Waterford took us to live with them, and brought us up with their own four little daughters. Harriet, their oldest girl, was two years younger than I, and Elizabeth, the youngest, was just the age of Betty Jane. When cousins agree at all, they agree better than sisters, and we were all extraordinarily happy. The Ramsays were our nearest neighbors; their place, Bonnie Brae, sat on the same hilltop as ours—a houseful of lonely men (and such strange ones!) tyrannized over by a Swedish woman who was housekeeper.

Greenacre was a little railway station where every evening dogcarts and carriages drew up and waited for the express that brought the business men down from the City, and then rolled them along smooth roads to their dwellings, scattered about on the fine line of hills, clad with forest, that rose above a historic American river.

The City up the river it is scarcely necessary to name; a big inland American manufacturing city, older and richer and gloomier than most, also more powerful and important. Greenacre was not a suburb in the modern sense. It was as old as the City, and there were no small holdings. The people who lived there had been born there, and inherited their land from fathers and grandfathers. Every householder had his own stables and pasture land, and hay meadows and orchard. There were plenty of servants in those days.

My Aunt Charlotte lived in the house where she was born, and ever since her marriage she had been playing with it and enlarging it, as if she had foreseen that she was one day to have a large family on her hands. She loved that house and she loved to work on it, making it always more and more just as she wanted it to be, and yet keeping it what it always had been—a big, rambling, hospitable old country house. As one drove up the hill from the station, Fox Hill, under its tall oaks and sycamores, looked like several old farmhouses pieced together; uneven roofs with odd gables and dormer windows sticking out, porches on different levels connected by sagging steps. It was all in the dull tone of scaling brown paint and old brown wood—though often, as we came up the hill in the late afternoon, the sunset flamed wonderfully on the diamond-paned windows that were so gray and inconspicuous by day.

The house kept its rusty outer shell, like an old turtle's, all the while that it was growing richer in color and deeper in comfort within. These changes were made very cautiously, very delicately. Though my aunt was constantly making changes, she was terribly afraid of them. When she brought things back from Spain or Italy for her house, they used to stay in the barn, in their packing cases, for months before she would even try them. Then some day, when we children were all at school and she was alone, they would be smuggled in one at a time—sometimes to vanish forever after a day or two. There was something she wanted to get, in this corner or that, but there was something she was even more afraid of losing. The boldest enterprise she ever undertook was the construction of the new music-room, on the north side of the house, toward the Ramsays'. Even that was done very quietly, by the village workmen. The piano was moved out into the big square hall, and the door between the hall and the scene of the carpenters' activities was closed up. When, after a month or so, it was opened again, there was the new music-room, a proper room for chamber music, such as the petty kings and grand dukes of old Germany had in their castles; finished and empty, as it was to remain; nothing to be seen but a long room of satisfying proportions, with many wax candles flickering in the polish of the dark wooden walls and floor.

It was into this music-room that Aunt Charlotte called Harriet and me one November afternoon to tell us that Valentine Ramsay was coming home. She was sitting at the piano with a book of Debussy's piano pieces open before her. His music was little known in America then, but when she was alone she played it a great deal. She took a letter from between the leaves of the book. There was a flutter of excitement in her voice and in her features as she told us: "He says he will take the next fast steamer after his letter. He must be on the water now."

"Oh, aren't you happy, Aunt Charlotte!" I cried, knowing well how fond she was of him.

"Very, Marjorie. And a little troubled too. I'm not quite sure that people will be nice to him. The Oglethorpes are very influential, and now that Janet is living here—"

"But she's married again."

"Nevertheless, people feel that Valentine behaved very badly. He'll be here for Christmas, and I've been thinking what we can do for him. We must work very hard on our part songs. Good singing pleases him more than anything. I've been hoping he may fall into the way of composing again while he's with us. His life has been so distracted for the last few years that he's almost given up writing songs. Go to the playroom, Harriet, and tell the little girls to get their school work done early. We'll have a long rehearsal tonight. I suppose they scarcely remember him."

Three years before Valentine Ramsay had been at home for several weeks before his brother Horace died. Even at that sad time his being there was like a holiday for us children, and all the Greenacre people seemed glad to have him back again. But much had happened since then. Valentine had deserted his wife for a singer, notorious for her beauty and misconduct; had, as my friends at school often told me, utterly disgraced himself. His wife, Janet Oglethorpe, was now living in her house in the City. I had seen her twice at Saturday matinées, and I didn't wonder that Valentine had run away with a beautiful woman. The second time I saw her very well—it was a charity performance, and she was sitting in a box with her new husband, a young man who was the perfection of good tailoring, who was reputed handsome, who appeared so, indeed, until you looked closely into his vain, apprehensive face. He was immensely conceited, but not sure of himself, and kept arranging his features as he talked to the women in the box. As for Janet, I thought her an unattractive, red-faced woman, very ordinary, as we said. Aunt Charlotte murmured in my ear that she had once been better looking, but that after her marriage with Valentine she had grown stouter and "coarsened"—my aunt hurried over the word.

Aunt Charlotte had never, I knew, approved of the marriage. When he was a little boy Valentine had been her squire and had loved her devotedly. After his mother died, leaving him in a houseful of grown men, she had looked out for him and tried to direct his studies. She was ten years older than Valentine, and, in the years when Uncle Harry came a-courting, the spoiled neighbor boy was always hanging about and demanding attention. He had a pretty talent for the piano, and for composition; but he wouldn't work regularly at anything, and there was no one to make him. He drifted along until he was a young fellow of twenty, and then he met Janet Oglethorpe.

Valentine had a habit of running up to the City to dawdle about the Steinerts' music store and practice on their pianos. The two young Steinert lads were musical and were great friends of his. It was there, when she went in to buy tickets for a concert, that Janet Oglethorpe first saw Valentine and heard him play. He was a strikingly handsome boy, and picturesque— certainly very different from the canny Oglethorpe men and their friends. Janet took to him at once, began inviting him to the house and asking musicians there to meet him. The Ramsays were greatly pleased; the Oglethorpes were the richest family in a whole cityful of rich people. They owned mines and mills and oil wells and gas works and farms and banks. Unlike some of our great Scotch families, they didn't become idlers and coupon-clippers in the third generation. They held their edge—kept their keenness for money as if they were just beginning, must sink or swim, and hadn't millions behind them. Janet was one of the third generation, and it was well known that she was as shrewd in business as old Duncan himself, the founder of the Oglethorpe fortune, who was still living, having buried three wives, and spry enough to attend directors' meetings and make plenty of trouble for the young men.

Janet was older than Valentine in years, and much older in experience and judgment. Even after she had announced her engagement to him, Aunt Charlotte prevailed upon him to go abroad to study for a little. He was happily settled in Paris, under Saint-Saëns, but before the year was out Janet followed him up and married him. They lived abroad. Aunt Charlotte had visited them in Rome, but she never said much about them.

Later, when the scandal came, and everyone in the City, and in Greenacre as well, fell upon Valentine for a worthless scamp, Uncle Harry and Aunt Charlotte always stood up for him, and said that when Janet married a flighty student she took the chance with her eyes open. Some of our friends insisted that he had shattered himself with drink, like so many of the Ramsay men; others hinted that he must "take something," meaning drugs. No one could believe that a man entirely in his right mind would run away from so much money—toss it overboard, mills and mines, stocks and bonds; and that when he had none himself, and Bonnie Brae was plastered with mortgages, and old Uncle Jonathan had already two helpless men to take care of.

II

For ten days after his letter came we waited and waited for Valentine. Everyone was restless—except Uncle Jonathan, who often told us that he enjoyed anticipation as much as realization. Uncle Morton, Valentine's much older brother, used to stumble in of an evening, when we were all gathered in the big hall after dinner, to announce the same news about boats that he had given us the evening before, wave his long thin hands a little, and boast in a husky voice about his gifted brother. Aunt Charlotte put her impatience to some account by rehearsing us industriously in the part songs we were working up for Valentine. She called us her sextette, and she trained us very well. Several of us were said to have good voices. My aunt used to declare that she liked us better when we were singing than at any other time, and that drilling us was the chief pleasure she got out of having such a large family.

Aunt Charlotte was the person who felt all that went on about her—and all that did not go on—and understood it. I find that I did not know her very well then. It was not until years afterward, not until after her death, indeed, that I began really to know her. Recalling her quickly, I see a dark, full-figured woman, dressed in dark, rich materials; I remember certain velvet dresses, brown, claret-colored, deep violet, which especially became her, and certain fur hats and capes and coats. Though she was a little overweight, she seemed often to be withdrawing into her clothes, not shrinking, but retiring behind the folds of her heavy cloaks and gowns and soft barricades of fur. She had to do with people constantly, and her house was often overflowing with guests, but she was by nature very shy. I now believe that she suffered all her life from a really painful timidity, and had to keep taking herself in hand. I have said that she was dark; her skin and hair and eyes were all brown. Even when she was out in the garden her face seemed always in shadow.

As a child I understood that my aunt had what we call a strong nature; still, deep and, on the whole, happy. Whatever it is that enables us to make our peace with life, she had found it. She cared more for music than for anything else in the world, and after that for her family and her house and her friends. She was very intelligent, but she had entirely too much respect for the opinions of others. Even in music she was often dominated by people who were much less discerning than she, but more aggressive. If her preference was disputed or challenged, she easily gave up. She knew what she liked, but she was apt to be apologetic about it. When she mentioned a composition or an artist she admired, or spoke the name of a person or place she loved, I remember a dark, rich color used to come into her voice, and sometimes she uttered the name with a curious little intake of the breath.

Aunt Charlotte's real life went on very deep within her, I suspect, though she seemed so open and cordial, and not especially profound. No one ever thought of her as intellectual, though people often spoke of her wonderful taste; of how, without effort, she was able to make her garden and house exactly right. Our old friends considered taste as something quite apart from intelligence, instead of the flower of it. She read little, it is true; what other people learned from books she learned from music,—all she needed to give her a rich enjoyment of art and life. She played the piano extremely well; it was not an accomplishment with her, but a way of living. The rearing of six little girls did not seem to strain her patience much. She allowed us a great deal of liberty and demanded her own in return. We were permitted to have our own thoughts and feelings, and even Elizabeth and Betty Jane understood that it is a great happiness to be permitted to be glad or sorry in one's own way.

III

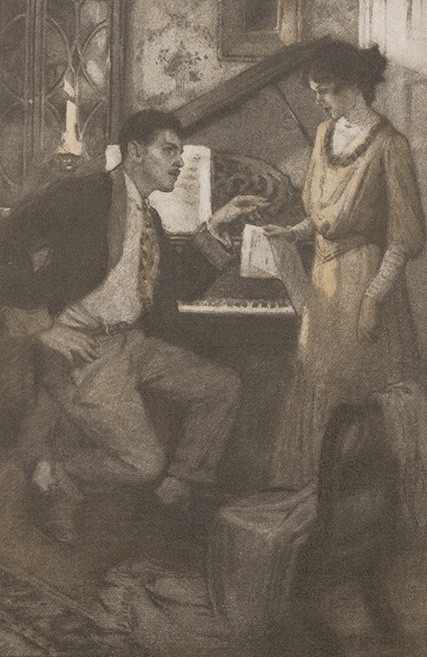

"I was so excited that I made a poor show at reading the

manuscript"

"I was so excited that I made a poor show at reading the

manuscript"

On the night of Valentine's return, our household went in a body over to Bonnie Brae to make a short call. It was delightful to see the old house looking so festive, with lights streaming from all the windows. We found the family in the long, pale parlor; the men of the house, and half a dozen Ramsay cousins with their wives and children.

Valentine was standing near the fireplace when we entered, beside his father's armchair. The little girls at once tripped down the long room toward him, Uncle Harry following. But Aunt Charlotte stopped short in the doorway and stood there in the shadow of the curtains, watching Valentine across the heads of the company, as if she wished to remain an outsider. Through the buzz and flutter of greetings, his eyes found her there. He left the others, crossed the room in a flash, and, giving her a quick, sidewise look, put down his head to be kissed, like a little boy. As he stood there for a moment, so close to us, he struck me at once as altogether too young to have had so much history, as very hardy and high-colored and unsubdued. His thick, seal-brown hair grew on his head exactly like fur, there was no part in it anywhere. His short mustache and eyebrows had the same furry look. His red lips and white teeth gave him a striking freshness—there was something very roguish and wayward, very individual about his mouth. He seldom looked at one when he talked to one—he had a habit of frowning at the floor or looking fixedly at some object when he was speaking, but one felt his eyes through the lowered lids—felt his pleasure or his annoyance, his affection or impatience.

Since gay Uncle Horace died the Ramsay men did not often give parties, and that night they roamed about somewhat uneasily, all but Uncle Jonathan, who was always superbly at his ease. He kept his arm-chair, with a cape about his shoulders to protect him from drafts. The old man's hair and beard were just the color of dirty white snow, and he was averse to having them trimmed. He was a gracious host, having the air of one to whom many congratulations are due. Roland had put on a frock coat and was doing his duty, making himself quietly agreeable to everyone. His handsome silver-gray head and fine physique would have added to the distinction of any company. Uncle Morton was wandering about from group to group, jerking his hands this way and that—a curiously individual gesture from the wrist, as if he were making signals from a world too remote for speech. He fastened himself upon me, as he was very likely to do (finding me out in the little corner sofa to which I had retreated), sat down beside me and began talking about his brother in disconnected sentences, trying to focus his almost insensible eyes upon me.

"My brother is very devoted to your aunt. She must help me with his studio. We are going to make a studio for him off in the wing, for the quiet. Something very nice. I think I shall have the walls upholstered, like cushions, to keep the noise out. It will be handsome, you understand. We can give parties there—receptions. My brother is a fine musician. Could play anything when he was eleven—classical music—the most difficult compositions." In the same expansive spirit Uncle Morton had once planned a sunken garden for my aunt, and a ballroom for Harriet and me.

Molla Carlsen brought in cake and port and sherry. She had been at the door to admit us, and had since been intermittently in the background, disappearing and reappearing as if she were much occupied. She had always this air of moving quietly and efficiently in her own province. Molla was very correct in her deportment, was there and not too much there. She was fair, and good looking, very. The only fault Aunt Charlotte had to find with her appearance was the way she wore her hair. It was yellow enough to be showy in any case, and she made it more so by parting it very low on one side, just over her left ear, indeed, so that it lay across her head in a long curly wave, making her low forehead lower still and giving her an air that, as some of our neighbors declared, was little short of "tough."

After we had sipped our wine the cousins began to gather up their babies for departure, and we younger ones had all to go up to Uncle Jonathan and kiss him good night. It was a rite we shrank from, he was always so strong of tobacco and snuff, but he liked to kiss us, and there was no escape.

When we left, Uncle Valentine put his arm through Aunt Charlotte's and walked with us as far as the summerhouse, looking about him and up overhead through the trees. I heard him say suddenly, as if it had just struck him:

"Isn't it funny, Charlotte; no matter how much things or people ought to be different, what we love them for is for being just the same!"

IV

The next afternoon when Harriet and I got home from Miss Demming's school, we heard two pianos going, and knew that Uncle Valentine was there. The door between the big hall and the music-room was open, and Aunt Charlotte called to us:

"Harriet and Marjorie? Run upstairs and make yourselves neat. You may have tea with us presently."

When we came down, the music had ceased, and the hall was empty. Black John, coming through with a plate of toast, told us he had taken tea into the study.

My uncle's study was my favorite spot in that house full of lovely places. It was a little room just off the library, very quiet, like a little pond off the main currents of the house. There was but one door, and no one ever passed through it on the way to another room. As it had formerly been a conservatory for winter flowers, it was all glass on two sides, with heavy curtains one could draw at night to shut out the chill. There was always a little coal fire in the grate, Uncle Harry's favorite books on the shelves, and the new ones he was reading arranged on the table, along with his pipes and tobacco jars. Sitting beside the red coals one could look out into the great forking sycamore limbs, with their mottled bark of white and olive green, and off across the bare tops of the winter trees that grew down the hill slopes—until finally one looked into nothingness, into the great stretch of open sky above the river, where the early sunsets burned or brooded over our valley. It was with delight I heard we were to have our tea there.

We found my aunt and Valentine before the grate, the steaming samovar between them, the glass room full of gray light, a little warmed by the glowing coals.

"Aren't you surprised to find us here?" There was just a shade of embarrassment in my aunt's voice. "This was Uncle Valentine's choice." Curious; though she always looked so at ease, so calm in her matronly figure, a little thing like having tea in an unusual room could make her a trifle self-conscious and apologetic.

Valentine, in brown corduroys with a soft shirt and a Chinese-red necktie, was sitting in Uncle Harry's big chair, one foot tucked under him. He told us he had been all over the hills that morning, clear up to Flint Ridge. "I came home by the near side of Blinker's Hill, past the Wakeley place. I wish Belle wouldn't stay abroad so long; it's a shame to keep that jolly old house shut up." He said he liked having tea in the study because the outlook was the same as from his upstairs room at home. "I was always supposed to be doing lessons there as evening came on. I'm sure I don't know what I was doing writing serenades for you, probably, Charlotte."

Aunt Charlotte was nursing the samovar along—it never worked very well. "I've been hoping," she murmured, "that you would bring me home some new serenades—or songs of some kind."

"Songs? Oh, hell, Charlotte!" He jerked his foot from under him and sat up straight. "Sorry I swore, but you evidently don't know what I've been up against these last four years. You'll have to know, and so will your maidens fair. Anyhow, if you're to have a rake next door to a houseful of daughters, you'd better look into it."

Aunt Charlotte caught her breath painfully, glanced at Harriet and me and then at the door. Valentine sprang up, went to the door and closed it. "Oh, don't look so frightened!" he exclaimed irritably, "and don't send the girls away. Do you suppose they've heard nothing? What do you think girls whisper about at school, anyway? You'd better let me explain a little."

"I think it unnecessary," she murmured entreatingly.

"It isn't unnecessary!" he stamped his foot down upon the rug. "You mean they'll think what you tell them to—stay where you put them, like china shepherdesses. Well, they won't!"

We were almost as much frightened as Aunt Charlotte. He was standing before us, his brow wrinkled in a heavy frown, his shoulders lowered, his red lips thrust out petulantly. I am sure I was hoping that he wouldn't quite explain away the legend of his awful wickedness. As he addressed us he looked not at us but at the floor.

"You've heard, haven't you, Harriet and Marjorie, that I deserted a noble wife and ran away with a wicked woman? Well, she wasn't a wicked woman. She is kind and generous, and she ran away with me out of charity, to get me out of the awful mess I was in. The mess, you understand, was just being married to this noble wife. Janey is all right for her own kind, for Oglethorpes in general, but she was all wrong for me.

Here he stopped and made a wry face, as if his pedagogical tone put a bad taste in his mouth. He glanced at my aunt for help, but she was looking steadfastly at the samovar.

"Hang it, Charlotte," he broke out, "these girls are not in the nursery! They must hear what they hear and think what they think. It's got to come out. You know well enough what dear Janey is; you've known ever since you stayed with us in Rome. She's a common, energetic, close-fisted little tradeswoman, who ought to be keeping a shop and doing people out of their eyeteeth. She thinks, day and night, about common, trivial, worthless things. And what's worse, she talks about them day and night. She bargains in her sleep. It's what she can get out of this dressmaker or that porter; it's getting the royal suite in a hotel for the price of some other suite. We left you in Rome and dashed off to Venice that fall because she could get a palazzo at a bargain. Some English people had to go home on account of a grandmother dying and had to sub-let in a hurry. That was her only reason for going to Venice. And when we got there she did nothing but beat the house servants down to lower wages, and get herself burned red as a lobster staying out in boats all day to get her money's worth. I was dragged about the world for five years in an atmosphere of commonness and meanness and coarseness. I tell you I was paralyzed by the flood of trivial, vulgar nagging that poured over me and never stopped. Even Dickie—I might have had some fun with the little chap, but she never let me. She never let me have any but the most painful relations with him. With two nurses sitting idle, she'd make me chase off in a cab to demand his linen from special laundresses, or scurry around a whole day to find some silly kind of milk—all utter nonsense. The child was never sick and could take any decent milk. But she likes to make a fuss; calls it 'managing.'

"Sometimes I used to try to get off by myself long enough to return to consciousness, to find whether I had any consciousness left to return to—but she always came pelting after. I got off for Bayreuth one time. Thought I'd covered my tracks so well. She arrived in the middle of the Ring. My God, the agony of having to sit through music with that woman!" Valentine sat down and wiped his forehead. It glistened with perspiration; the roots of his furry hair were quite wet.

After a moment he said doggedly, "I give you my word, Charlotte, there was nothing for it but to make a scandal; to hurt her pride so openly that she'd have to take action. I don't know that she'd have done it then, if Seymour Towne hadn't turned up to sympathize with her. You can't hurt anybody as beefy as that without being a butcher!" He shuddered.

"Louise Ireland offered to be the sacrifice. She hadn't much to lose in the way of—well, of the proprieties, of course. But she's a glorious creature. I couldn't have done it with a horrid woman. Don't think anything nasty of her, any of you, I won't have it. Everything she does is lovely, somehow or other, just as every song she sings is more beautiful than it ever was before. She's been more or less irregular in behavior—as you've doubtless heard with augmentation. She had certainly run away with desperate men before. But behavior, I find, is more or less accidental, Charlotte. Oh, don't look so scared! Your dovelets will have to face facts some day. Æsthetics come back to predestination, if theology doesn't. A woman's behavior may be irreproachable and she herself may be gross—just gross. She may do her duty, and defile everything she touches. And another woman may be erratic, imprudent, self-indulgent if you like, and all the while be—what is it the Bible says? Pure in heart. People are as they are, and that's all there is to life. And now—" Valentine got up and went toward the door to open it.

Aunt Charlotte came out of her lethargy and held up her finger. "Valentine," she said with a deep breath, "I wasn't afraid of letting the girls hear what you had to say—not exactly afraid. But I thought it unnecessary. I understood everything as soon as I looked at you last night. One hasn't watched people from their childhood for nothing."

He wheeled round to her. "Of course you would know! But these girls aren't you, my dear! I doubt if they ever will be, even with luck!" The tone in which he said this, the proud, sidelong glance he flashed upon her, made this a rich and beautiful compliment—so violent a one that it seemed almost to hurt that timid woman. Slowly, slowly, the red burned up in her dark cheeks, and it was a long while dying down.

"Now we've finished with this—what a relief!" Valentine knelt down on the window seat between Harriet and me and put an arm lightly around each of us. "There's a fine sunset coming on, come and look at it, Charlotte."

We huddled together, looking out over the descending knolls of bare tree tops into the open space over the river, where the smoky gray atmosphere was taking on a purple tinge, like some thick liquid changing color. The sun, which had all day been a shallow white ring, emerged and swelled into an orange-red globe. It hung there without changing, as if the density of the atmosphere supported it and would not let it sink. We sat hushed and still, living in some strong wave of feeling or memory that came up in our visitor. Valentine had that power of throwing a mood over people. There was nothing imaginary about it; it was as real as any form of pain or pleasure. One had only to look at Aunt Charlotte's face, which had become beautiful, to know that.

It was Uncle Harry who brought us back into the present again. He had caught an early train down from the City, hoping to come upon us just like this, he said. He was almost pathetically eager for anything of this sort he could get, and was glad to come in for cold toast and tea.

"Awfully happy I got here before Valentine got away," he said, as he turned on the light. "And, Charlotte, how rosy you are ! It takes you to do that to her, Val." She still had the dusky color which had been her unwilling response to Valentine's compliment.

V

Within a few days Uncle Valentine ran over to beg my aunt to go shopping with him. Something had reminded him that Christmas was very near.

"It's awfully embarrassing," he said. "Nobody in Paris was saying anything about Christmas before I sailed. Here I've come home with empty trunks, and Paris full of things that everybody wants."

Aunt Charlotte laughed at him and said she thought they would find plenty of things from Paris up in the City.

The next morning Valentine appeared before we left for school. He was in a very businesslike mood, and his check book was sticking out from the breast pocket of his fur coat. They were to catch the eight-thirty train. The day was dark and gray, I remember, though our valley was white, for there had been a snowfall the day before. Standing on the porch with my school satchel, I watched them get into the carriage and go down the hill as the train whistled for the station below ours—they would just have time to catch it. Aunt Charlotte looked so happy. She didn't often have Valentine to herself for a whole day. Well, she deserved it.

I could follow them in my mind: Valentine with his brilliant necktie and foreign-cut clothes, hurrying about the shops, so lightning-quick, when all the men they passed in the street were so slow and ponderous or, when they weren't ponderous, stiff—stiff because they were wooden, or because they weren't wooden and were in constant dread of betraying it. Everybody would be trying not to look at bright-colored, foreign-living, disgracefully divorced Valentine Ramsay; some in contempt—some in secret envy, because everything about him told how free he was. And up there, nobody was free. They were imprisoned in their harsh Calvinism, or in their merciless business grind, or in mere apathy—a mortal dullness.

Oh, I could see those two, walking about the narrow streets of the grim, raw, dark gray old city, cold with its river damp, and severe by reason of the brooding frown of huge stone churches that loomed up even in the most congested part of the shopping district. There were old grave-yards round those churches, with gravestones sunken and tilted and blackened—covered this morning with dirty snow—and jangling car lines all about them. The street lamps would be burning all day, on account of the fog, full of black smoke from the furnace chimneys. Hidden away in the grime and damp and noise were the half dozen special shops which imported splendors for the owners of those mills that made the city so dark and so powerful.

Their shopping over, Valentine was going to take Aunt Charlotte to lunch at a hotel where they could get a very fine French wine she loved. What a day they would have! There was only one thing to be feared. They might easily chance to meet one of the Oglethorpe men, there were so many of them, or Janet herself, face to face, or her new husband, Seymour Towne, who had been the idle son of an industrious family, and by idling abroad had stepped into such a good thing that now his hard-working brothers found life bitter in their mouths.

But they didn't meet with anything disagreeable. They came home on the four-thirty train, before the rush, bringing their spoils with them (no motor truck deliveries down the valley in those days), and their faces shone like the righteous in his Heavenly Father's house. Aunt Charlotte admitted that she was tired and went upstairs to lie down directly after tea. Valentine took me down into the music-room to show me where to put the blossoming mimosa tree he had found for Aunt Charlotte, when it came down on the express tomorrow. The little girls followed us, and when he told them to be still they crept into the corners.

Valentine sat down at the piano and began to play very softly; some-thing dark and rich and shadowy, but not somber, with a silvery air flowing through its mysteriousness. It might, I thought, be something of Debussy's that I had never heard…but no, I was sure it was not.

Presently he rose abruptly to go without taking leave, but one of the little girls ran up to him—Helen, probably, she was the most musical—and asked him what he had been playing, please.

"Oh, some old thing, I guess. I wasn't thinking," he muttered vaguely, and escaped through the glass doors that led directly into the garden between our house and his. I felt very sure that it was nothing old, but something new—just beginning, indeed. That would be a pleasant thing to tell Aunt Charlotte. I ran upstairs; the door of her room was ajar, but all was dark within. I entered on tiptoe and listened; she was sound asleep. What a day she had had!

VI

Aunt Charlotte planned a musical party for Christmas eve and invited a dozen or more of her old friends. They were coming home with her after the evening church service; we were to sing carols, and Uncle Valentine was to play. She telephoned the invitations, and made it very clear that Valentine Ramsay was going to be there. Whoever didn't want to meet him could decline. Nobody declined; some even said it would be a pleasure to hear him play again.

On Christmas eve, after dinner, Uncle Harry and I were left alone in the house. All the children went to the church with Aunt Charlotte; she left me to help Black John arrange the table for a late supper after the music. After I had seen to everything, I had an hour or so alone upstairs in my own room.

I well remember how beautiful our valley looked from my window that winter night. Through the creaking, shaggy limbs of the great sycamores I could look off at the white, white landscape ; the deep folds of the snow-covered hills, the high drifts over the bushes, the gleaming ice on the broken road, and the thin, gauzy clouds driving across the crystal-clear, star-spangled sky.

Across the garden was Bonnie Brae, with so many windows lighted; the parlor, the library, Uncle Jonathan's room, Morton's room, a yellow patch on the snow from Roland's window, which I could not see; off there, at the end of the long, dark, sagging wing, Valentine's study, lit up like a lantern. I often looked over at our neighbors' house and thought about how much life had gone on in it, and about the muted, mysterious lives that still went on there. In the garret were chests full of old letters; all the highly descriptive letters that Uncle Jonathan had written his wife when he was traveling abroad; family letters, love letters, every letter the boys had written home when they were away at school. And in all these letters were tender references to the garden, the old trees, the house itself. And now so many of those who had loved the old place and danced in the long parlor were dead. I wondered, as young people often do, how my elders had managed to bear life at all, either its killing happiness or its despair.

I heard wheels on the drive, and laughter. Looking out I saw guests alighting on one side of the house, and on the other side Uncle Valentine running across the garden, bareheaded in the snow. I started downstairs with a little faintness at heart—I knew how much my aunt had counted on bringing Valentine again into the circle of her friends, under her own roof. I found him in the big hall, surrounded by the ladies they hadn't yet taken off their wraps—and I surveyed them from the second landing where the stairway turned. They were doing their best, I thought. Some of the younger women kept timidly at the outer edge of the group, but all the ones who counted most were emphatic in their cordiality. Deaf old Mrs. Hungerford, who rather directed public opinion in Greenacre, patted him on the back, shouted that now the naughty boy had come home to be good, and thrust out her ear trumpet at him. Julia Knewstubb, who for some reason, I never discovered why, was an important person, stood beside him in a brassy, patronizing way, and Ida Milholland, the intellectual light of the valley, began speaking slow, crusty French at him. In short, all was well.

Salutations over, Aunt Charlotte led the way to the music-room and signaled to her six girls. We sang one carol after another, and a fragment of John Bennett's we had especially practiced for Uncle Valentine—a song about a bluebird flying over a gray landscape and making it all blue; a pretty thing for high voices. But when we finished this and looked about to see whether it had pleased him, Valentine was nowhere to be found. Aunt Charlotte drew me aside while the others went out to supper and told me I must search all through the house, go to Bonnie Brae if necessary, and fetch him. It would never do for him to behave thus, when they had unbent so far as to come and greet him.

I looked out of the window and saw a light in his study at the end of the wing. The rooms between his study and the main house were unused, filled with old furniture. He avoided that chain of dusty, echoing chambers and came and went by a back door that opened into the old apple orchard. I dashed across the garden and ran in upon him without knocking.

There he was, lounging before the fire in his slippers and wine-colored velvet jacket, a pipe in his mouth and a yellow French book on his knee. I gasped and explained to him that he must come at once; the company was waiting for him.

He shrugged and waved his pipe. "I'm not going back at all. Pouf, what's the use? I'd only behave badly if I did. I don't want to lose my temper on Christmas eve."

"But you promised Aunt Charlotte, and she's told them you'd play," I pleaded.

He flung down his book wrathfully. "Oh, I can't stand them! I didn't know who Charlotte was going to ask…seems to me she's got together all the most objectionable old birds in the valley. There's Julia Knewstubb, with her nippers hanging on her nose, looking more like a horse than ever. Old Mrs. Hungerford, poking her ear trumpet at me and stroking me on the back—I can't talk into an ear trumpet can't think of anything important enough to say! And that bump of intellect, Ida Milholland, creaking at every joint and practicing her French grammar on me. Charlotte knows I hate ugly women—what did she get such a bunch together for? Not much, I'm not going back. Sit down and I'll read you something. I've got a new collection of all the legends about Tristan and Iseult. You can understand French?"

I said I would be dreadfully scolded if I did such a thing. "And you will hurt Aunt Charlotte's feelings, terribly!"

He laughed and poked out his red lower lip at me. "Shall I? Oh, but I can mend them again! Listen, I've got a new song for her, a good one. You sit down, and we'll work a spell on her; we'll wish and wish, and she'll come running over. While we wait I'll play it for you."

He put his pipe on the mantel, went to the piano, and commenced to play the Ballad of the Young Knight, which begins:

"From the Ancient Kingdoms, Through the wood of dreaming,…"It was the same thing I had heard him trying out the afternoon he and Aunt Charlotte got home from the City.

"Now, you try it over with me, Margie. It's meant for high voice, you see. By the time she comes, we can give her a good performance."

"But she won't come, Uncle Valentine! She can't leave her guests."

"Oh, they'll soon be gone! Old tabbies always get sleepy after supper—you said they were at supper. She'll come."

I was so excited, so distressed and delighted, that I made a poor showing at reading the manuscript, and was well scolded. Valentine always wrote the words of his songs, as well as the music, like the old troubadours, and the words of this one were beautiful. "And what wood do you suppose it is?" He played the dark music with his left hand.

I said it made me think of the wood on the other side of Blinker's Hill.

"I guess so," he muttered. "But of course it will be different woods to different people. Don't tell Charlotte, but I'm doing a lot of songs. I think of a new one almost every morning, when I waken up. Our woods are full of them, but they're terribly, terribly coy. You can't trap them, they're too wild….No, you can't catch them…sometimes one comes and lights on your shoulder; I always wonder why."

It did not seem very long until Aunt Charlotte entered, bareheaded, her long black cape over her shoulders, a look of distress and anxiety on her face. Valentine sprang up and caught her hand.

"Not a word, Charlotte, don't scold, look before you leap! I kept Margie because I knew you'd come to hunt her, and I didn't just know any other way of getting you here. Now don't be angry, because when you get angry your face puffs up just a little, and I have reason to hate women whose faces swell. Sit down by the fire. We've had a rehearsal, and now we'll sing my new song for you. Don't glare at the child, or she can't sing. Why haven't you taught her to follow manuscript better?"

Aunt Charlotte didn't have a chance to speak until we had gone through with the song. But though my eyes were glued to the page, I knew her face was going through many changes.

"Now," he said exultantly as we finished, "with a song like that under my shirt, did I have to sit over there and let old Ida wise-bump practice her French on me—period of Bossuet, I guess!"

Aunt Charlotte laughed softly and asked us to sing it again. The second time we did better; Valentine hadn't much voice, but of course he knew how. As we finished we heard a queer sound, something like a snore and something like a groan, in the wall behind us. Valentine held up his finger sharply, tiptoed to the door behind the fireplace that led into the old wing, put down his head and listened for a moment. Then he wrenched open the door.

There stood Roland, holding himself steady by an old chest of drawers, his eyes looking blind, tears shining on his white face. He did not say a word; put his hands to his forehead as if to collect himself, and went away through the dark rooms, swaying slightly and groping along the floor with his feet.

"Poor old chap, perfectly soaked! I thought it was Molla Carlsen, spooking round." Valentine threw himself into a chair. "Do you suppose that's the way I'll be keeping Christmas ten years from now, Charlotte? What else is there for us to do, I ask you? Sons of an easy-going, self-satisfied American family, never taught anything until we are too old to learn. What could Roland do when he came home from Germany fifteen years ago?…Lord, it's more than that now…it's nineteen! Nineteen years!" Valentine dropped his head into his hands and rumpled his hair as if he were washing it, which was a sign with him that a situation was too hopeless for discussion. "Well, what could he have done, Charlotte? What could he do now? Teach piano, take the bread out of somebody's mouth? My son Dickie, he'll be an Oglethorpe! He'll get on, and won't carry this damned business any farther."

On Christmas morning Molla Carlsen came over and reported with evident satisfaction that Roland and Valentine had made a night of it, and were both keeping their rooms in consequence. Aunt Charlotte was sad and downcast all day long.

[ TO BE CONCLUDED IN THE MARCH ISSUE]